Fighting the Water Crises in Appalachia and Beyond

This mountaintop removal coal strip mine in Boone County, West Virginia is one of over 500 such sites in the state, dramatically demonstrating the process of recovering coal after first blasting thousands of tons of rock, foliage and other debris from the mountaintop to gain easier access. This destructive extraction technique is much cheaper than underground mining with fewer human safety concerns, but also far fewer workers.

The overburden is the name given to the fractured tons of rock. After blasting, it is dumped into the valleys separating one mountain from another, filling countless streams and altering not only the topography forever, but also devastating the foliage and fauna. The exposed coal seams can then be easily harvested with huge strip mining machinery. Such valley fill can be observed in the flyover.

The blasted rock over time leaches toxic amounts of organic elements into these smothered streams and eventually into the groundwater of everything in its path including private wells and aquifers. In documented studies, the contaminants in these waters result in higher rates of various cancers, infant mortality, and neurological complications.

Before coal is shipped, it must be washed and the toxic residues from this process are collected in large retention ponds that have the potential for leakage into the groundwater and even possible failure and consequential flooding and contamination. Notice several ponds in the flyover.

The Surface Mining Control and Reclamation Act (SMCRA) of 1977 is the primary federal law regulating the environmental effects of coal mining in the United States, and mine operators are required to reclaim the damaged mountains to as close to a natural state, contour, and habitat as possible. However, individual states have the authority to override Federal law, issuing waivers for operator-proposed changes in land usage and agreeing to limited reclamation which is shown in the video by seeded terraces void of trees or other natural foliage. Unfortunately, the moonscape as shown in the video more often are representative of the outcome.

Urgent News

This mountaintop removal coal strip mine in Boone County, West Virginia is one of over 500 such sites in the state, dramatically demonstrating the process of recovering coal after first blasting thousands of tons of rock, foliage and other debris from the mountaintop to gain easier access. This destructive extraction technique is much cheaper than underground mining with fewer human safety concerns, but also far fewer workers.

The overburden is the name given to the fractured tons of rock. After blasting, it is dumped into the valleys separating one mountain from another, filling countless streams and altering not only the topography forever, but also devastating the foliage and fauna. The exposed coal seams can then be easily harvested with huge strip mining machinery. Such valley fill can be observed in the flyover.

The blasted rock over time leaches toxic amounts of organic elements into these smothered streams and eventually into the groundwater of everything in its path including private wells and aquifers. In documented studies, the contaminants in these waters result in higher rates of various cancers, infant mortality, and neurological complications.

Before coal is shipped, it must be washed and the toxic residues from this process are collected in large retention ponds that have the potential for leakage into the groundwater and even possible failure and consequential flooding and contamination. Notice several ponds in the flyover.

The Surface Mining Control and Reclamation Act (SMCRA) of 1977 is the primary federal law regulating the environmental effects of coal mining in the United States, and mine operators are required to reclaim the damaged mountains to as close to a natural state, contour, and habitat as possible. However, individual states have the authority to override Federal law, issuing waivers for operator-proposed changes in land usage and agreeing to limited reclamation which is shown in the video by seeded terraces void of trees or other natural foliage. Unfortunately, the moonscape as shown in the video more often are representative of the outcome.

Water is Life: This Is How You Can Improve Its Quality

Each day it is crucial that adults consume at least half of their body weight in ounces of water. In other words, if you weigh

Leaving no one behind – The United Nations World Water Development

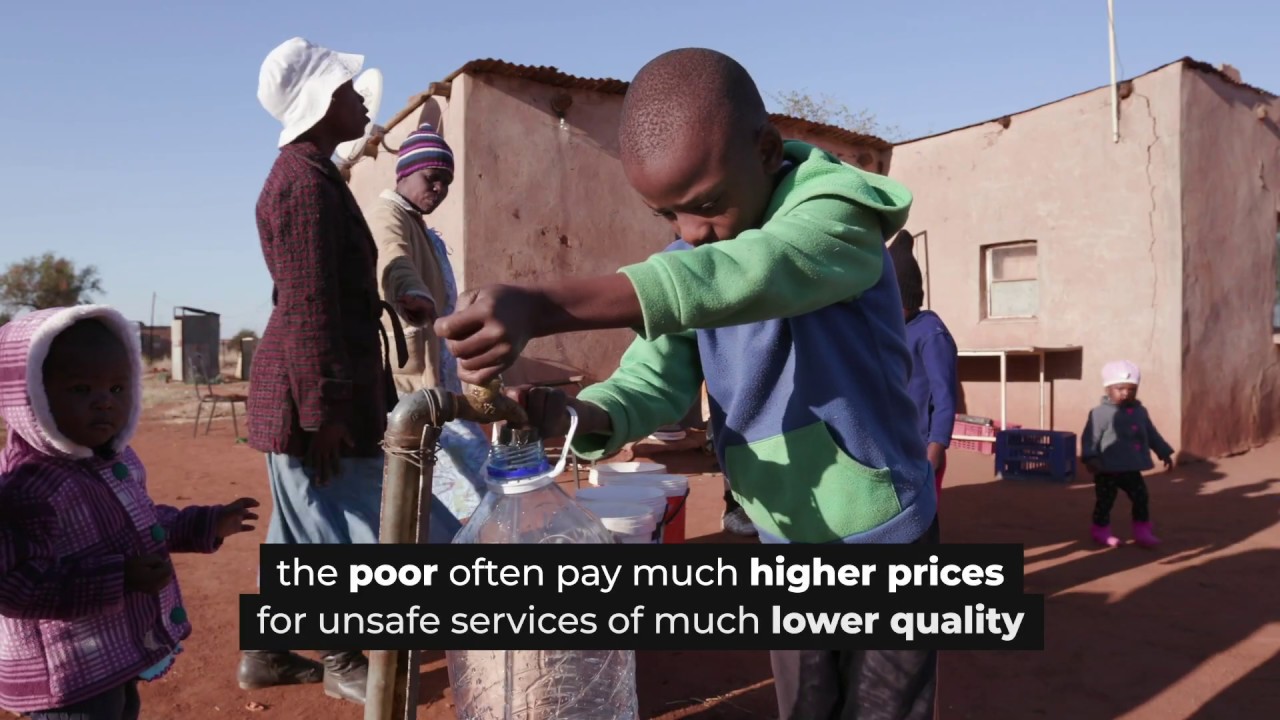

As water demand increases proportionally with global population growth, it is the poor and disadvantaged who suffer disproportionally.

Political

CLEAN WATER

POISON IS NEXT

How Federal Institutions Follow the Clean Waters Act

The main federal law in charge of the improvement and upkeep of our nation’s waters is the Clean Waters Act (CWA). Its primary objective is

“When the well is dry, we’ll know the worth of water.”

– Benjamin Franklin