Coal Mining

Changes in Water Has Lead To Increase in Health Risks

Much of the population in Appalachia are scattered about the valleys, hollows, and mountainsides — the distance and geography too difficult for municipal water systems to reach. So for generations, the primary water sources for these people have been owner-maintained private wells that have, for the most part, provided a reliable and safe drinking supply.

Changes not only in the wells but also in the streams, began to occur in the 1980s. Tap water began to turn red, then black. Clothes began to stain grey when washed. Creeks ran white, green, red, orange, then white again. Plumbing fixtures began to corrode. Children began to develop chronic illnesses at a very early age, even losing teeth prematurely. Clusters of certain cancers, gastrointestinal, neurological, respiratory, and dermatological illnesses began appearing in before-unseen numbers in both young and elderly alike.

A common link between illnesses and coal mining appears to be contaminated well water that harbors heavy metals such as lead, arsenic, and mercury in toxic levels that far exceeded EPA danger thresholds.

Research and anecdotal evidence is pointing to a new method of mining as a contributor to sudden spikes in illnesses.

The Dangers of Mountain Top Removal

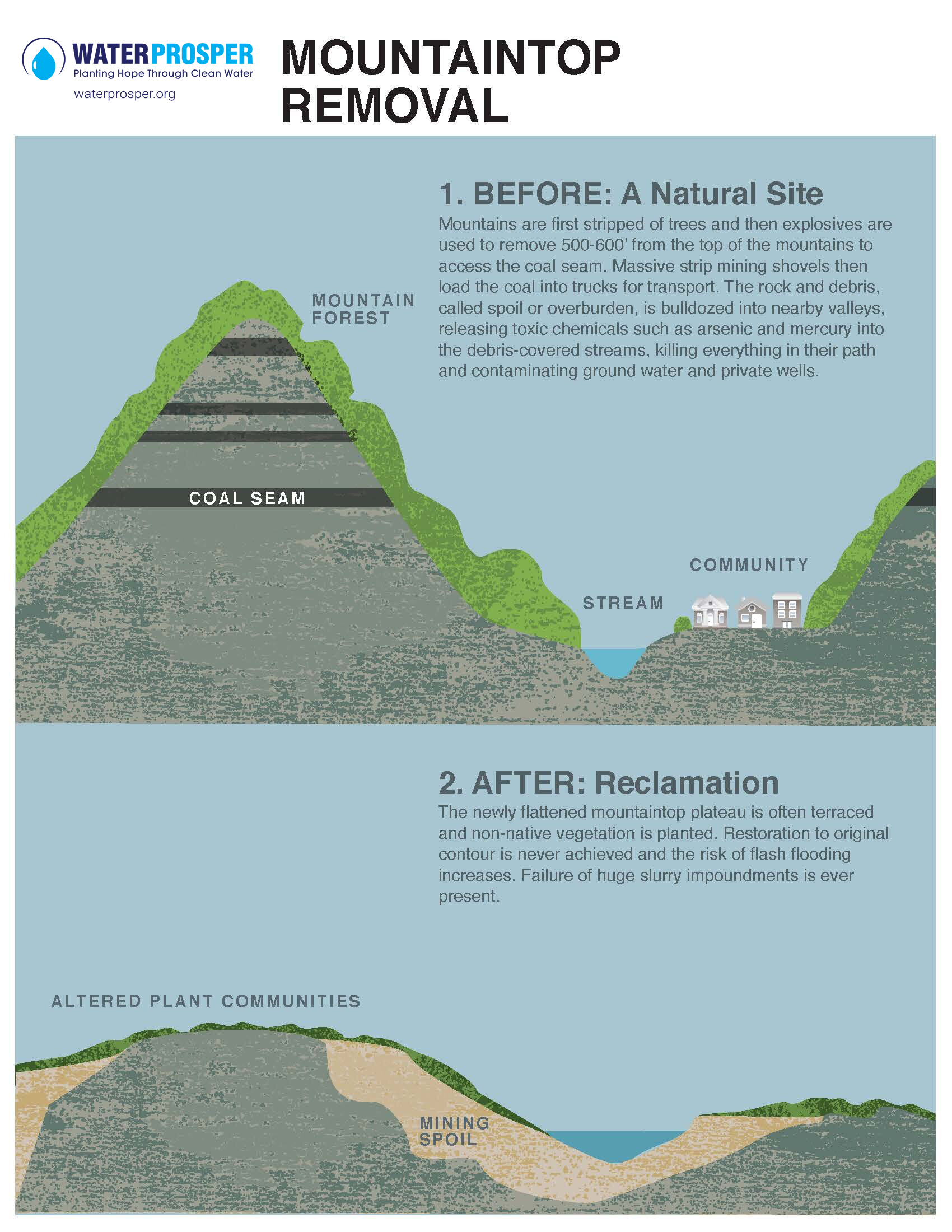

A few years earlier, mountaintop removal (MTR) of coal became a prominent method of extraction. In the decades that followed, MTR became the less expensive method of accessing coal, especially in those areas where the easily-accessed 6-8’ thick underground seams had long since been harvested. Much larger excavation machines, far fewer miners, and a great reduction of expensive underground mine equipment all contributed to a more robust bottom line for those companies transitioning to mountaintop removal.

In MTR, entire tops of Appalachian mountains are removed by detonation, and this overburden, or spoil, is dumped into the valleys, covering the streams. Varying amounts of heavy metals, including lead, mercury, arsenic, selenium, strontium, aluminum, manganese, and magnesium, leach from this vast amount of fractured rock into both surface and ground waters.

Coal Slurry and It’s Toxins

The other coal extraction activity potentially affecting human health and the environment is the by-product of both underground mining and mountaintop removal. Prior to being loaded into trucks, railcars, and barges for shipment to power plants, toxic coal dust is removed at prep facilities using millions of gallons of fresh water mixed with organic chemicals. The byproduct of this ‘washing’ is black coal slurry or sludge, that is pumped into immense earthen-damned reservoirs called impoundment ponds.

According to an EPA surface impoundment database, the twelve largest containments in West Virginia alone have a capacity of 12 billion gallons and cover a combined area of 643 acres.

Many of these earthen-damned impoundment ponds loom high above and in dangerously close proximity to communities huddled in the valleys and strung along the hollows.

Contaminant Failures Disasters

Through the years, there have been containment failures sometimes resulting in catastrophic flash flooding, such as the 1972 Buffalo Creek disaster. After a dam collapsed, a twenty-five-foot high fast-moving wall of thick sludge surged through a narrow valley resulting in a large loss of life and property in twelve small communities. As a final legacy of the disaster, toxic residues soaked into the soil, the creeks, and surviving buildings threatening the inhabitants’ health for years to come.

Coal companies have also turned to pumping the toxic slurry into abandoned underground coal mines where, unfortunately, the contaminants leach out of the mine shafts and into the aquifers and surface waters. Along with a host of other harmful inorganic chemicals, water escaping the abandoned mines contains iron and magnesium creating acid mine drainage and loss of aquatic life in hundreds of miles of creeks and streams.

Throughout Appalachia, more than 500 mountaintops have been leveled. In West Virginia alone, the tops of more than 200 mountains, or 1.47 million acres, have already been blown off and subsequently bulldozed into valleys, filling in an estimated 2,000 miles of streams and eliminating fragile flora and fauna.

Created from this process are massive plateaus, some resembling moonscapes. Most are seeded with grasses and various vegetation to meet the minimum state-approved restoration requirements, but they never return to their original forested native state or contour.